With the exciting news in March of the Asheville Art Museum’s new acquisitions of two James Ormsbee Chapin studies for the Collection’s 1942—1945 painting Nine Workmen, it made me curious. Who are these nine men and what work are they doing? This question is also relevant in relation to the current exhibition, Our Strength is Our People: The Humanist Photographs of Lewis Hine. Chapin, like Lewis Hine, and many artists of the 1930s and 1940s, chose the common American and their everyday activities as their primary focus. The style of Chapin’s painting is known as American Scene painting, a naturalistic approach that placed more importance on portraying the subject in a realistic, representational manner than it did on emulating a popular European style of art, like Impressionism or Cubism. (Coincidentally it became a style all its own.) Drawing on the tradition of the Ashcan School of painting and documentary photography of the time, the American Scene movement was also often referred to as Regionalism, because it was produced in a particular region by an artist with firsthand knowledge of it. Alternatively, photographers working in journalism or documentation at the time, like Hine, were often assigned to photograph urban scenes, life on a farm, or working conditions outside of their own neighborhood or even state. But in both cases, the artists were trying to truly capture the essence of American life. In the case of Nine Workmen, an interesting history of workers and labor unions in New Jersey emerges.

The workmen depicted were likely based on individuals from Chapin’s home state of New Jersey. The artist lived just north of Trenton—between Allentown, PA and Edison, NJ—in the “rust belt” of America, a center of booming industry and manufacturing in the United States. With shovels, wheelbarrows, and other tools in hand, these men were possibly construction workers. At the time of this painting and just before, during the Great Depression, industry in New Jersey was on the decline, but construction was on the rise. As part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Works Progress Administration, many new construction jobs were created in this area, including the building of Roosevelt Park in Edison and Rutgers Stadium in Piscataway, NJ. Another interesting hypothesis is that these workers could have been gravediggers. In 1937 a group of 40 gravediggers in North Arlington, NJ held a sit-down strike and prevented burials from taking place in order to secure raises for the groundskeepers. American workers had formed unions since the mid-19th century in response to the Industrial Revolution; unions helped secure better wages and set limits on weekly working hours. During the Great Depression, the government promoted the right of unions to organize with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935. While it was meant to promote collective bargaining, it also led to an increase in strikes, like that of the North Arlington Gravediggers Association. The range in ages of the Nine Workmen could also allude to the human life span and symbolize the passage of time. If Chapin was commenting on the rights of workers, then his style of American Scene painting may more closely align with the Social Realists who addressed politics and social problems in the US at the time. This would also link Chapin’s work more closely to that of Hine’s, whose employment by progressive foundations focused his efforts on improving the social wellness of the American people. Another social aspect of Nine Workmen is the inclusion of a Black workman. Between 1916 and 1970 more than six million African Americans left the South and relocated north in search of better paying jobs and to escape Jim Crow laws that allowed for racial segregation, discrimination, and violence. Other paintings by Chapin that hint towards his social activism include Laborers at Lunch (1923), Quarry Workers (1934), his series of paintings depicting the Scottsboro Boys Trial painted from 1946 to 1974, and a portrait of Supreme Court justice and civil rights activist Thurgood Marshall (1955).

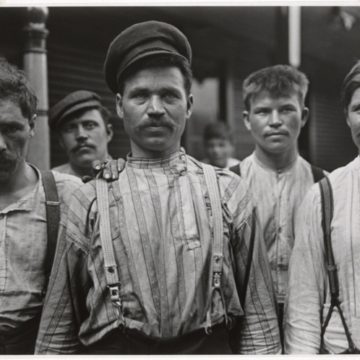

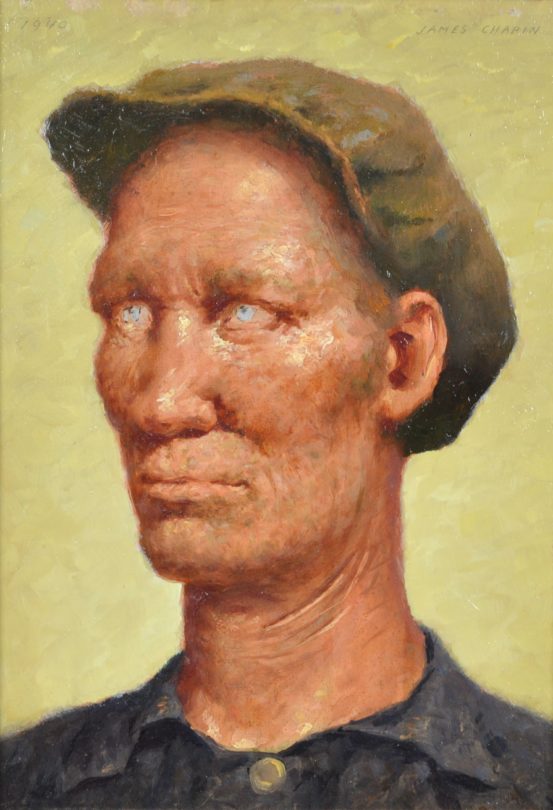

Nine Workmen was painted between 1942 and 1945 as indicated in the lower left corner of the painting next to Chapin’s signature. But the new acquisition of two head studies, a drawing and painting, indicates that he started creating preparatory imagery for the final Nine Workmen painting at least as early as 1940. Many of the men’s faces in this large-scale painting appeared before and after in Chapin’s other works, as well, so they were potentially models or people known to him. As a viewer looking at Chapin’s work today, it’s exciting to see these familiar faces again and again. Much like Hine’s labor portraits—particularly his photograph of Steel Workers at Russian Boarding House (1908) featured in Our Strength is Our People—the hard work and difficult lives of the Nine Workmen are illustrated in Chapin’s depiction of their drawn and tired faces. Chapin and Hine were both utilizing these workers’ expressions and postures to offer a Humanist perspective on the face of laborers and in the process have kept them alive, in spirit, for nearly a century as the people who built this country.

—Whitney Richardson, associate curator

James Ormsbee Chapin, Untitled (Head of Laborer), 1940, oil on board, 19 1/4 × 15 1/2 inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by David Shurbutt in memory of his son, Kai, 2021.01.01. © The Estate of James Ormsbee Chapin.

James Ormsbee Chapin, Untitled (Head of Laborer), 1940, oil on board, 19 1/4 × 15 1/2 inches. Museum purchase with funds provided by David Shurbutt in memory of his son, Kai, 2021.01.01. © The Estate of James Ormsbee Chapin.