“Black Mountain’s contribution was that you could live creatively simply by the way you looked at life and the way you lived it. I didn’t learn technique at Black Mountain [College]. I learned a point of view.” —Mary Gregory

Following her graduation in the first class from Bennington College and a five-year stint teaching at the Cambridge School of Weston in Massachusetts, Mary “Molly” Gregory arrived at Black Mountain College (BMC) in 1941 as an apprentice-teacher with the intention to study with Josef Albers. She quickly rose through the ranks to instructor of crafts, and then took over the woodshop from Robert Bliss when many of the male students and faculty joined the war effort in 1942. Gregory was eventually reappointed the title of instructor of woodworking from 1943 until her departure in 1947, at which point two farming couples were employed to attempt to fill the immense void of her absence.

Gregory was a powerhouse—she managed the woodshop and ran the farm including its bookkeeping while teaching, and additionally directed several summer work camps between 1945 and 1946. She oversaw the completion of the Studies Building, and then guided students through the process of building their own furniture to outfit their studios. Most of the major furniture pieces—such as the large table in the classroom of the studies building and all the benches for the Quiet House—were fabricated by Gregory, and nearly all the furnishings across the campus and farm were made in the woodshop under her instruction.

The marriage of form and function in Gregory’s furniture design and fabrication is among many reasons that her work endures. These pieces, and all of Gregory’s furniture from Black Mountain College, feel both useful and beautiful. They align with the William Morris ideal that one should ”Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” Functional as seating, the stools may be combined in versatile arrangements to serve as low tables, stacked into pedestal or lectern forms, or combined as workbenches. Materials were scarce at BMC, especially during wartime when much of the farm property was built, and many of the architectural structures were made of lumber sourced from the Lake Eden campus property. Overall, vernacular, accessible materials were used but occasionally some finer materials were sourced for specific finishing details, such as wormy chestnut in the hallway of the Studies Building which took over four years to complete due to lack of funds and scarcity of wormy chestnut. Gregory was very conscious of material usage and the symbiotic relationship with the land, and in the Black Mountain College Bulletin 5, no.4 (May 1947), Gregory notes that “Forty-five hundred small trees have been planted on the eroded and steep parts of the mountain pasture [on the Lake Eden Property]; locusts, balsam, white pine: reforestation.”

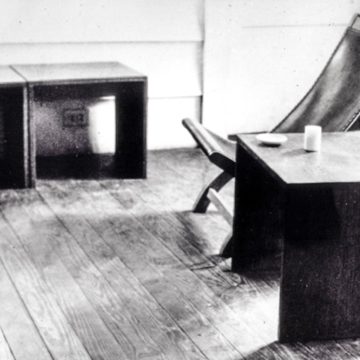

The works in the Museum’s Collection represent the minimalist, modular stool design Gregory made for wide use at BMC (one of six in the Collection) as well as a chair Gregory fabricated based on a design by Albers. The minimalist stools are comprised of three planes of stained oak joined by dove-tail joints, with an apron connecting the two sides by mortise and tenon joints. Each side is made from two joined slabs of wood, which are likely glued to one another to create the full width of the slab.

The stools bear the marks of wear, long-term usage, and life. Theodore Dreier Sr. was a co-founder of BMC along with John Andrew Rice, and these stools were used by the Dreier family in their home in Black Mountain until Dreier’s departure from BMC in 1949 when they moved to New York and then to Martha’s Vineyard, bringing the Gregory furniture with them.

The stained ash, leather, and brass of the Lazy-J bears these marks as well, and itself belongs in a legacy of both extraction and homage. It was designed by Albers but influenced by a reimagined 16th-century Mexican chair design by Clara Porset in the 1930s, who Albers met on one of his many trips to Mexico in the 1940s.

Gregory’s furniture is grouped in a vignette in the Butler Gallery within the SECU Collection Hall with a Ruth Asawa sculpture, which was constructed in 1954. Asawa’s wire sculpture bears reference to the visual language clearly developed during her time at BMC as evidenced by BMC Stamp (Wallpaper) circa 1953, on view to the right of this sculptural vignette in the Chaddick Foundation Gallery.

In a speech given at the BMC reunion at Bard College on April 11, 1987, Gregory shared these moving thoughts about her time at BMC:

“It isn’t a great jump to become fascinated by how each job we do—be it being a farmer, a woodworker, or musician, or machine operator—calls for the same scrutiny, the same excitement in finding how all these skills (or needs) may be used to make one’s own contribution, perhaps even in a new way. It’s one thing to have a glimpse of the possibilities, but it’s another to be in a place where this insight may be tried and even used, and best of all, needed. It’s tremendously exciting to be in an environment where you are called to use all of your faculties in every direction.”

Gregory lived to be 92 and passed peacefully at the New England Friends Home in Hingham, MA, on November 21, 2006.

—Lydia See, 2020 curatorial fellow

Mary “Molly” Gregory, Lazy-J Chair, circa 1945, stained ash, leather, and brass, 26 ¾ × 17 ⅛ × 24 ½ inches. Black Mountain College Collection, gift of Barbara Beate Dreier and Theodore Dreier Jr. on behalf of all generations of the Dreier family, 2017.12.02. © Mary Gregory, image David Dietrich.

Mary “Molly” Gregory, Stool, circa 1941–1945, stained oak, 15 ½ × 18 × 15 inches. Black Mountain College Collection, gift of Barbara Beate Dreier and Theodore Dreier Jr. on behalf of all generations of the Dreier family, 2017.12.05. © Mary Gregory, image David Dietrich.

Mary “Molly” Gregory, Lazy-J Chair, circa 1945, stained ash, leather, and brass, 26 ¾ × 17 ⅛ × 24 ½ inches. Black Mountain College Collection, gift of Barbara Beate Dreier and Theodore Dreier Jr. on behalf of all generations of the Dreier family, 2017.12.02. © Mary Gregory, image David Dietrich.

Mary “Molly” Gregory, Stool, circa 1941–1945, stained oak, 15 ½ × 18 × 15 inches. Black Mountain College Collection, gift of Barbara Beate Dreier and Theodore Dreier Jr. on behalf of all generations of the Dreier family, 2017.12.05. © Mary Gregory, image David Dietrich.