Imagine catching a 4:35pm train from Penn Station in New York City and arriving in Black Mountain, North Carolina at 8:35am the next morning, just in time for breakfast. The scenic journey along the Southern Railway was the recommended course of travel for students, faculty, and guests of Black Mountain College (BMC) coming from the Northeast. Included in this group were many of the participants of the 1943 “Seminar on America for Foreign Scholars,” advertised in this document from the Museum’s archives. A round trip ticket cost $29.92 per person with one transfer in Salisbury, NC. This also happened to be the same exact route that guests of George Vanderbilt took to Asheville for the infamous parties at the Biltmore Estate.

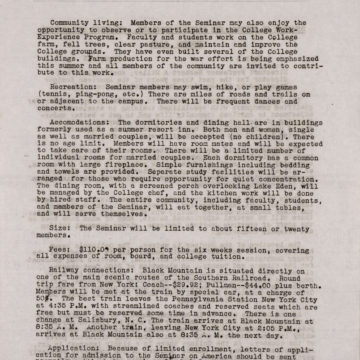

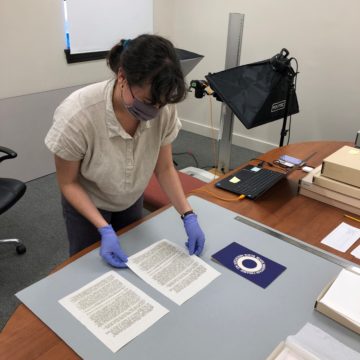

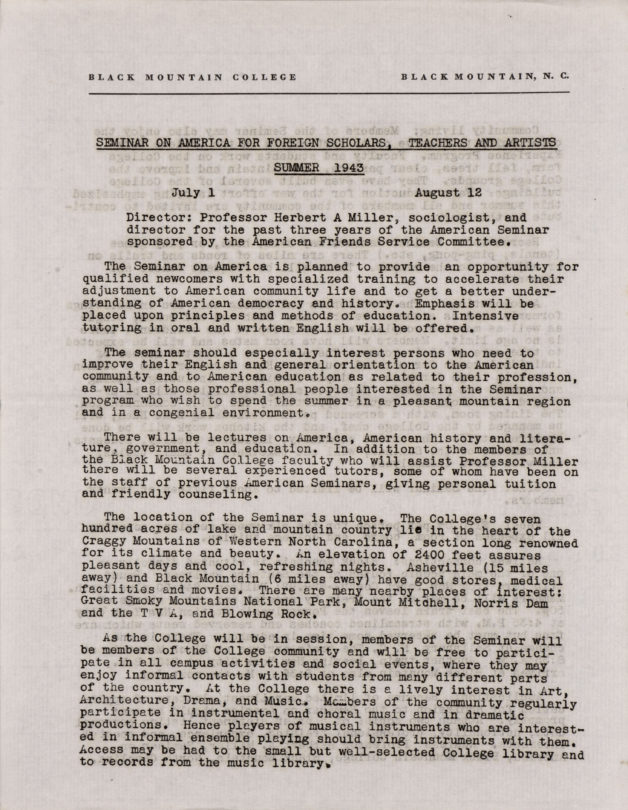

One of the great joys in assisting with the digitization project of the Museum’s extensive Black Mountain College Collection is the opportunity to spend time working with documents and ephemera that contribute to the understanding of the historical significance of BMC as well as the works of art created there. This mimeograph, for example, invited applications for the six-week “Seminar on America for Foreign Scholars” that took place at BMC in the summer of 1943 alongside the summer art and music institutes. Printed on BMC letterhead, the seminar was meant “to provide an opportunity for qualified newcomers with specialized training to accelerate their adjustment to American community life.” Programming included intensive English language training, various social events, and daily lectures on American history, literature, government, and education. Qualified political exiles and refugees from France, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Russia participated in the course. With so many central Europeans displaced by Nazi fascism during WWII, the American Seminar was meant to provide its attendants with necessary training responsive to the psychological and intellectual aspects of their adjustment to the United States.

The European tradition at BMC was well established years prior to the seminar. European emigrees participated as students and faculty since the college’s founding. The arts program was directed by Josef Albers who took the job at BMC in 1933 joined by his wife and master weaver, Anni Albers. Both had been faculty members at the German Bauhaus and their influence as artists and pedagogues ensured the success of the arts at BMC. In North Carolina, they maintained connections to a vast network of European intellectuals and modernists in America. Many were among those invited to visit, study, or teach in the various departments at BMC, representing the college’s role in the shift of place and production of the avant-garde from Europe to the United States and contributing to what curator Helen Molesworth has described as the school’s “cosmopolitan” sense of itself and its community.

Though the seminar was short and small—no more than fifteen to twenty qualified seminarians were hosted—its humble impact was significant and demonstrative of BMC’s institutional commitment and range of contribution to the war effort. Summaries of the seminar events can be found in weekly campus bulletins from July and August, which are also part of the Museum’s Collection. The summer’s activities included visits to the local community and promoted intellectual exchange and discussion around the status and experience of the immigrant. On one trip to All Soul’s Church in Biltmore Village, Reverend Isaac Northrup preached directly about the refugee experience in America and the need to welcome those affected by fascism. Afterwards, seminarians were invited to join congregants for dinner at homes in Asheville. This was exactly the sort of interchange that the director of the seminar, Herbert Miller, hoped it would foster. In addition to lectures and language study, seminarians also shared the freedom of telling their own stories and addressing the community with lectures on topics of their choosing.

In the best-case scenarios, institutions can provide shelter and solace for those who need it, but in the worst-case scenarios, just the opposite is true. By all accounts of those who attended, the American seminar afforded its participants a space and rare opportunity to ease into the adjustment that comes with immigration. Oliver Freud, son of famous Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud and attendee of the seminar, remarked upon his departure from BMC: “I think it is the moral and psychological atmosphere of the seminar which has been the most impressive factor of our short stay at BMC. All of us without exception . . . had to suffer, under an economis [sic] and political oppression, partly even deprived of our most essential civic rights, and we arrived in America in a mental condition not yet appropriate for the process of adaptation to a new country, so necessary for our future settling here . . .” (BMCCB August 16, 1943).

I like to think that Miller’s American seminar aligns with BMC’s demonstrated ability to change, morph, and respond to internal and external influences throughout its institutional existence. Chistopher Benfey, professor of English at Mount Holyoke College and, coincidentally, the great-nephew of Josef and Anni Albers, has convincingly argued that the demise of Black Mountain College after only 24 short but influential years of existence might be considered its most momentous and genius final act- however surprising that might sound. When colleges and universities in the United States depend so heavily on the constructed sense of permanence grounded in endowments, stone-pillared buildings, and high standings in annual rankings, the ephemeral nature of BMC represents a sharp juxtaposition that speaks volumes to the value of education beyond mere institutional preservation. Thus, Benfey’s reading seems especially hopeful to me. I celebrate BMC as a model of institutional flexibility and responsiveness, where the pursuit of learning and the exchange of ideas has outlived the institution itself.

— Corey Loftus, curatorial fellow fall 2021

Herbert A. Miller, Seminar on America for Foreign Scholars, Teachers and Artists Summer 1943, ink on paper, Black Mountain College Collection, Gift of Barbara Beate Dreier and Theodore Dreier, Jr. on behalf of all generations of Dreier family, 2017.40.263.

Herbert A. Miller, Seminar on America for Foreign Scholars, Teachers and Artists Summer 1943, ink on paper, Black Mountain College Collection, Gift of Barbara Beate Dreier and Theodore Dreier, Jr. on behalf of all generations of Dreier family, 2017.40.263.